The heart wants what it wants.

Follow your heart.

A loving heart is the truest wisdom.

Kind-hearted. Pounding heart. Heartbroken.

The heart been long been regarded as an organ of emotion.

The heart is not only central to our emotional system; it affects—and is affected—by what we feed our body (food, drink, movement) and our mind (thoughts, perceptions of reality).

Managing your emotions is key to building resilience and effectively coping with stress, which can go a long way toward improving heart health.

Valentine’s Day celebrates the emotion of love, traditionally associated with the heart. Since 1963, February (the entire month) has also been dedicated to raising awareness about heart health. In the U.S., heart disease is the #1 killer of both men and women. Approximately 610,000 Americans die of heart disease every year; that’s 1 in every 4 deaths.1

But we should be mindful of our heart health beyond February.

Managing our emotions is essential for a healthy heart. However, since unexpressed, repressed or negative emotions can manifest as physical symptoms, it is also important to understand the physical risk factors for heart disease.

Physical Risk Factors for Heart Disease

Stereotype: The “typical” heart attack victim is a Type A (workaholic) male executive in his 50s.

Fact: Heart attacks are affecting younger people today. A study published recently in the medical journal, Circulation, found that the overall proportion of heart attack-related hospital admissions in the U.S, attributable to “young” patients (men and women aged 35 to 54) rose from 27% in 1995-99, to 32% in 2010-14, with the largest increase (from 21% to 31%) among young women.2

The reality is that the risk factors leading to heart disease can happen at ANY age.

These include:

Overweight and Obesity. Over 70% of American adults are overweight; of this 70%, 40% of American adults (more than 1 in 3) are obese, and 18.5% of children (apx. 1 in 6), ages 2 to 19, are obese. Extra weight puts stress on the heart.3

High blood pressure. Uncontrolled blood pressure increases risk of heart disease and stroke.

High cholesterol. Obesity, smoking, diabetes, physical inactivity and unhealthy food choices contribute to an increase in bad cholesterol.

Smoking. Smoking damages the blood vessels and can cause heart disease.

Diabetes. 1 in 10 Americans has diabetes, a condition where sugar builds up in the blood.

Lack of physical activity. Only 23.5% of Americans, 18 and older, meet the recommended guidelines for aerobic and strength-training activity.4

Excessive alcohol consumption. Heavy drinking or alcohol abuse can lead to heart failure, known as alcoholic cardiomyopathy, or alcohol toxicity to the heart muscle.5,6

Alcoholic cardiomyopathy is most common in men, ages 35 to 50, with a history of heavy, long-term (apx. 5 to 15 years) drinking. For men, “heavy drinking” is more than 4 drinks daily or more than 14 drinks per week. For women, heavy drinking is more than 3 drinks daily or more than 7 drinks per week.

Poor diet. Only 1 in 10 Americans eats the recommended 5-9 servings of fruits and vegetables every day. Diets high in unhealthy fats, sugar (added and/or artificial sweeteners), refined carbohydrates and processed foods increase risk of heart disease.7

Emotional Risk Factors for Heart Disease

In my practice, I see clients who often feel overwhelmed by stress.

No question about it: modern life is stressful. And negative emotions often drive our unhealthy food choices and lifestyle habits.

Feeling frustrated because you’re not getting the recognition you deserve at work? Maybe this is why you have an intimate relationship with comfort foods, like pizza, takeout Chinese and ice cream. Feeling trapped in an unhappy marriage or job? Maybe it feels more bearable when you pound wine or cocktails every night. Feeling angry because you feel like you do 85% of the work at work—and at home? Maybe that’s why you look forward to zoning out in front of the television (until 1 or 2 AM) after the kids are in bed. Feeling anxious because your latest entrepreneurial venture tanked? Maybe it feels like smoking or vaping helps calm your anxiety.

Chronic, negative emotions can feed inflammation and adversely affect heart health. These include:

Anxiety or anxiety disorder (e.g., panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder). Anxiety may be associated with rapid heart rate, increased blood pressure and decreased heart rate variability.8

Anger. Studies have suggested that outbursts of anger or episodes of intense anger can increase the risk of heart attack, stroke or other cardiovascular events.9

Stress. Emotional stress can lead to behaviors and factors that increase your risk of heart disease: overeating, lack of exercise, drinking alcohol and smoking can lead to high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Depression. Depression is common in people with heart disease or who have undergone a coronary artery bypass.10 However, depression, itself, is an independent risk for heart disease—even without known heart disease.11

Grief. Heart attack risk can increase significantly during the days and weeks after the death of a loved one.12 Stress, caused by intense grief, can increase heart rate, blood pressure and blood clotting, raising chances of a heart attack. At the beginning of the grieving process, people are more likely to experience less sleep, low appetite and higher cortisol (a stress hormone) levels, which can also increase heart attack risk.13

Even if you don’t have heart disease or you’ve never had a heart attack, emotional stress still affects your heart. For example, in a 1997 study, researchers monitored EKG (electrocardiograph) changes in healthy physicians during emergency calls while they were on hospital duty. The EKG changes that occurred before and during the first 30 seconds of an emergency call indicated oxygen deprivation and abnormal heart rhythms.14

A 2016 study, published in Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, explored the brain-heart connection. Researchers found that negative emotions (considered “brain-based”), such as stress, anger and depression, can increase the frequency of heart arrhythmias (irregular heart beat).15

An earlier study found that depression—whether major or minor—is a risk factor for a fatal cardiac event. Even in people without prior heart disease, major depression (versus minor) doubles the risk of dying from heart-related causes.16

The Heart, Emotions and Stress

The heart and brain have a two-way communication system.

Our thoughts or emotional state can greatly affect our physical well-being.

The heart has its own “brain” and nervous system, which send signals to the brain (in the head), influencing how the brain processes emotions and cognitive function, including attention, perception, memory and problem-solving.17

When we experience a specific feeling or thought, it affects our autonomic nervous system (ANS) by releasing neuropeptides, nerve proteins that link perception in the brain to the body and emotions. The quality of the emotional signal our heart sends to our brain determines the type of chemicals our brain releases into our body. “Stress” is usually rooted in unmanaged negative emotions.18

For example, let’s say that you are going through a nasty divorce, including a custody battle. You feel fear and anxiety (the emotions at the root of your stress) about the outcome. This stress triggers the release of cortisol and adrenaline, two “fight-or-flight” stress hormones, in anticipation of a perceived danger. Cortisol and adrenaline “rally the troops” by sending energy to your muscles, increasing your heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rate, while, at the same time, shutting down digestion, reproduction, growth and immunity (unimportant metabolic processes if your body is preparing to flee a tiger!).

When your body is in continual high-alert “EMERGENCY!” mode, these stress hormones and neuropeptides can cause health problems, from high blood pressure and digestive issues, to problems with your memory, immune system—and your heart.

Studies conducted by HeartMath Institute, a non-profit organization specializing in emotional physiology, resilience and stress management, show that emotions affect your heart rate variability (HRV), a measure of beat-to-beat changes in heart rate. Different patterns of heart activity influence cognitive and emotional function.19

For example, if you are under duress and experiencing negative emotions, such as anger, frustration and anxiety, your heart rhythm pattern will be irregular and chaotic (mirroring your feelings). This creates “distressed” neural signals, traveling from your heart to your brain, that limit cognitive function. This is why, under stress, you may act impulsively (e.g., go on an online shopping spree) or make rash (bad) decisions (e.g., drink and drive).

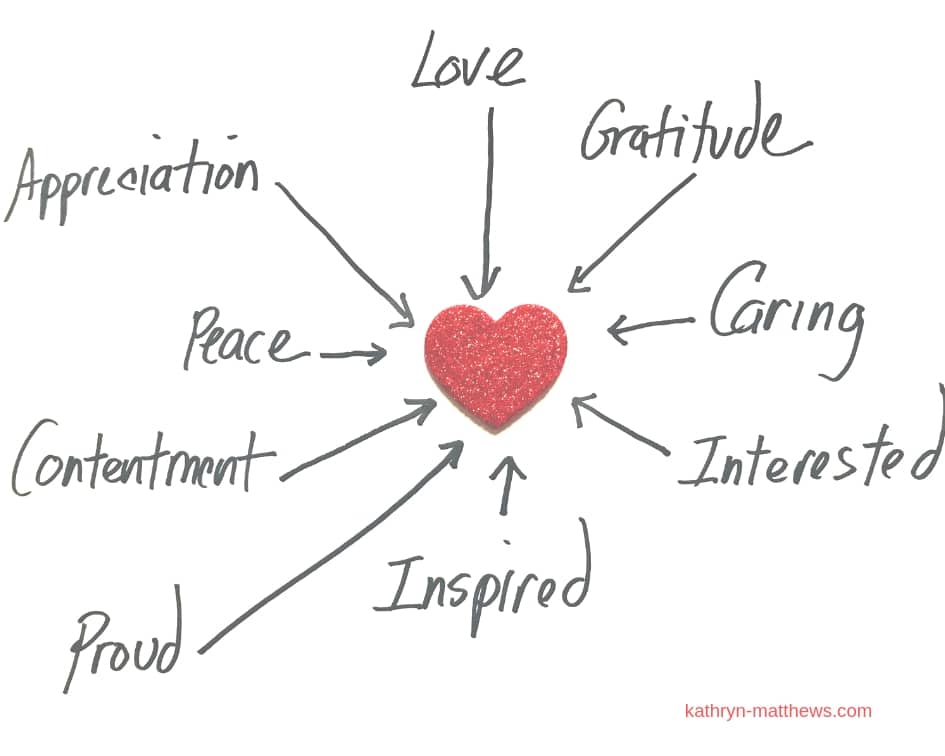

On the other hand, positive emotions, like gratitude, appreciation and caring, produce a regular, stable heart rhythm pattern. When the brain receives these harmonized neural signals, your stress hormones decrease, and your immune system is stronger. When you are in a positive emotional state, you will likely be thinking clearly and making effective (good) decisions.

The pattern of our HRV reflects how well we can adapt to stress; it serves as a marker of our physical resilience and our ability to change behavior (when necessary).20

How to Get (and Stay) on a Positive Emotional Track

Emotions are at the core of our “stress” experience. Our thoughts, too, tend to carry an emotional charge.

Neuroscience researchers have found that emotional processes operate at a higher speed than thought processes, and can bypass the mind’s linear reasoning process.21 As a result, what you think does not always result in how you feel.

This is why feeling positive involves more than just thinking positive.

So, how can we cultivate confidence, emotional positivity and emotional resilience?

By actually facing, acknowledging and moving through uncomfortable feelings.

Let’s face it: nobody wants to deal with painful, uncomfortable feelings. Most of us prefer to disconnect or distract ourselves from feeling bad. We do this by ignoring our feelings, doubting or questioning whether our feelings are even valid, and/or by engaging in addictive escapism behaviors (alcohol, drugs, overeating, binge-eating, compulsive shopping, electronic distractions, zoning out in front of the television)—anything that enables us to “check out”.

Even socially accepted behaviors, like exercising, being in constant multi-tasking “busy” mode, or being work-obsessed, can serve as distractions from uncomfortable feelings. In my past life as a freelance writer, I often dealt with my work-related feelings of frustration and anger by pounding my body with aggressive over-exercise (spending 2-3 hours at the gym). This “healthy” behavior—and my results—were praised; nonetheless, it was a distraction from what I was feeling inside. In the end, over-exercise drove my hormones into the ground and crashed my immune system.

In her illuminating new book, 90 Seconds to a Life You Love, psychologist Dr. Joan Rosenberg, gives practical guidance and strategies for creating emotional confidence and resilience. She writes:

“As paradoxical as it seems, the answer is tied to your capacity to tolerate pain—or your ability to handle unpleasant feelings. The more you are able to face the pain you experience, the more capable you become. The essential keys to developing confidence, feeling emotionally strong, and being resilient involve an openness to change, a positive attitude toward pain, a willingness to learn from any experience, and a capacity to experience and express unpleasant feelings.”

Her “Rosenberg Reset”, which helps you move through unpleasant feelings, is a simple 3-step formula: One choice. Eight feelings. 90 seconds.

- The “one choice” is to be present and to be aware of how you feel from moment-to-moment; this may include experiencing unpleasant feelings in the process.

- The eight common unpleasant feelings include: 1) sadness; 2) shame; 3) helplessness; 4) anger; 5) embarrassment; 6) disappointment; 7) frustration; and 8) vulnerability.

- You endure these unpleasant feelings by riding one or more 90-second waves of bodily sensations—like warm cheeks (e.g., feeling embarrassed), a pounding heart (e.g., feeling angry), or a heavy pit in the stomach (e.g., feeling deep disappointment)—that may accompany uncomfortable feelings. Pay attention: these physical sensations are how the body communicates our feelings to us.22

Rosenberg contends that major life choices—a spouse/partner; the “perfect” job, the college of your choice—can influence the opportunities we have in life, but not our overall happiness, sense of peace and well-being. Instead, she maintains, it is our moment-to-moment decisions that have a cumulative effect on our health and well-being.

For example, did you voice your true opinion at a work meeting? Did you trust your gut reaction on an awkward first date? Did you express how you really felt when a friend cancelled lunch last minute and rescheduled for the umpteenth time? All of these moment-to-moment decisions to address or ignore your feelings add up to how confident—and competent—you feel in navigating unpleasant emotions.23

It is like building an emotional “muscle” that, over time, enables you to speak your truth. By consistently experiencing and dealing with difficult feelings, Rosenberg maintains, you increase your capacity to engage in courageous conversations, which can enhance relationships and deepen the purpose and meaning of your life.

Perhaps, it only makes sense that the root of the word “courage” is “cor”, the Latin word for “heart”. And the original meaning of the word “courage” was “To speak one’s mind by telling all one’s heart”.

Sources:

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Heart Disease Facts.

2 Circulation. Nov. 2018; 139:1047–1056

3 AAFP.org

4 CDC. National Center for Health Statistis.

5 Herz. 2016; 41(6): 484–493.

6 Curr Atheroscler Rep.2008 Apr; 10(2): 117–120.

7 CDC: Division of Heart Disease & Stroke Prevention.

8 John Hopkins Medicine: Heart & Vascular Institute.

9 European Heart Journal. 2014 Jun 1; 35(21):1404-10.

10 Cleveland Clinic: Depression & Heart Disease.

11 University of Iowa Hospital & Clinics.

12 Science Daily. Jan. 10, 2012

13 Circulation. Jan. 9, 2012.

15 Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Vol. 30, Issue 3, July 1997, pp. 774-779

16 Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. Vol. 26. Issue 1. Jan. 2016, pp. 78-80.

17 Archives of General Psychiatry. Vol. 58, Issue 3, Mar 2001, pp. 221-227. University of Groningen.

19, 20 HeartMath Institute

18, 21 Stress in Health and Disease. Wiley-VCH. 2006.

22, 23 90 Seconds to a Life You Love. Joan I. Rosenberg. Little Brown. 2019.